Blog

Stories from my personal journey learning about and delivering Nature-rooted programs across three different countries

Considering Ecological Relationships, Impact, and Reciprocity in our Outdoor Programs

Caylin (Forest Schooled)

Empty space, drag to resize

Okay I have something to confess... it’s been a weight on my shoulders (and on my ecological conscience) as an environmental educator.

It’s about a hill. A small hill in the forest where the children loved to play and through their play, the hill was damaged. It was played on so much over the course of several months that not much of anything grew on it in the spring, while the hill right next to it flourished with new plant growth. The difference was so stark that it was obvious our play had directly reduced the area's ability to support other living things.

As an educator that delivers programs inherently connected with the Land, I am constantly trying to consider the impacts of our presence in the forest. After all, we are part of the ecological community that lives there. Where we place our feet as we walk, run, and play determines where plants are able or not able to grow. The sticks and logs that we move to build forts and other structures impact the animals that have sought refuge on, under, or inside them.

And I've noticed that the more time I've spent delivering programs and working with a particular place, the more my perspective has evolved with regards to my relationship and responsibility to the Land.

The change has manifested as a shift in how I think about and behave (and encourage children to consider how they think and behave) in relation to the natural world.

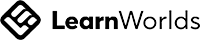

The shift has looked a little bit like this:

And then I remember that I'm forgetting a HUGE piece of the puzzle here. I'm missing the part about my relationship to the natural world before I grew up and started my career as an educator.... What was my relationship like when I was a child?

Asking that simple question brings a flood of memories back. I remember my curiosity in my own play as I crouched down to watch woodlice (affectionately called "roly polies") and how I would giggle as they rolled into a ball if I got too close. I remember "sleepy grass" which reacted even to the softest touch by closing its leaves tightly (i.e. "going to sleep"). I remember the birds hitting our living room windows and how I would run as fast as my little legs could take me to try to beat my cats to the place where they fell. I would scoop them up gently, protecting them from the prowling felines, to let them recover and fly off again (if they survived). I remember the chattering of the geckos on our walls and how they would abandon their tails as they darted away when you tried to catch one.

I understood that my actions, as a human, had an impact on the more-than-human beings that lived all around me. And when I brought home a bunch of fledging Francolin birds who appeared to be abandoned by their mother, I put them in a box to try to protect them. I felt a responsibility to look after them in their mother's absence. And I cried my little heart out when, despite my best efforts to keep them safe, they all died.

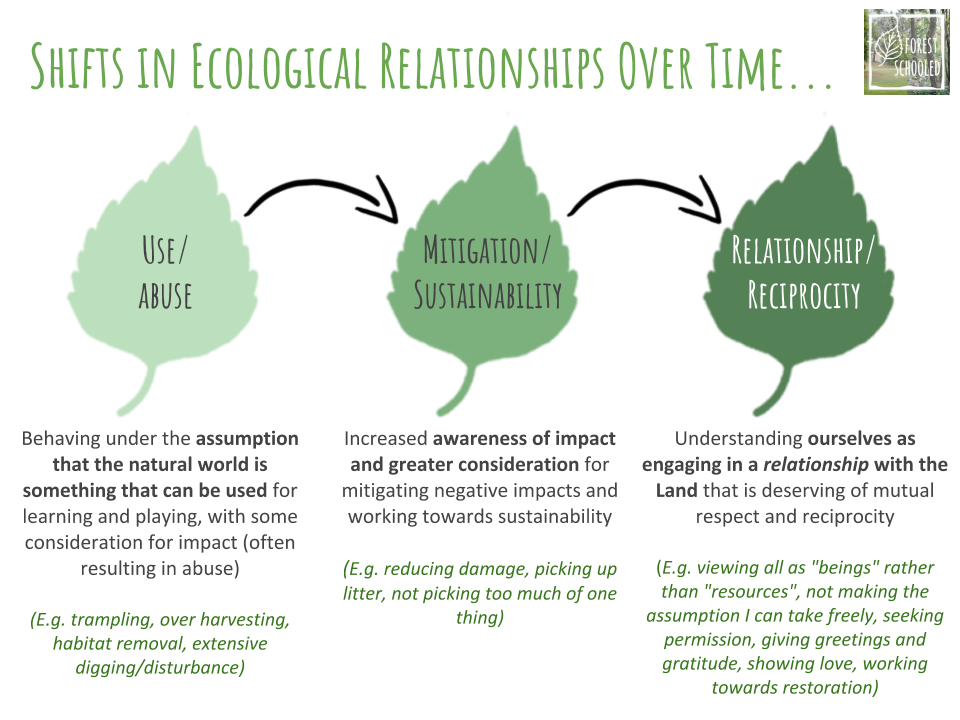

And so I've come to realize that my ecological relationship with the natural world has not been linear like I initially thought. It's actually been circular. I've returned to an understanding I had once held, innately, as a child. It was as I grew into adulthood that my natural tendency to view myself as a part of a reciprocal relationship with the natural world was socialized out of me. And so the shift has looked a little more like this:

I learned by observing and watching others around me that a reciprocal relationship with the natural world was thought of as unnecessary, or at least not a priority, and even straight up weird to some. So I buried that part of me... and it's been a process over the years of digging it back out again and piecing it firmly back into place.

And I want to emphasize that my experiences absolutely pale in comparison to those who have been subjected to violent oppression of cultural expression that has, and continues to, span multiple generations, like Indigenous, Black, and so many other marginalized people. This a valuable resource we can all access to learn more and work towards creating social and environmental justice.

So how does this apply to my work now?

Throughout this process of learning I've come to outwardly acknowledge how we can (and do) negatively impact the natural world when we play and learn outside (heck, we do it too when we're inside even if we don't see it directly - there's no way around it!). But in my mind there’s also a balance. Through continued play and exploration outdoors, there are also opportunities to grow awareness (for myself and the children) about our impacts, to learn what we can do about it, and to place attention on ways to give back and make the relationship we have with the Land more reciprocal.

Yes we take, use, and sometimes damage during our programs. But we can also repair, nurture, and express gratitude. These are aspects I’ve been consciously trying to place more emphasis on in my practice because, to me, they help maintain the balance.

These are a handful of ways I've been working on my ecological relationships:

- Listening to the perspectives of Indigenous people across the globe who've been fighting for and defending the Land for centuries. Reading Natural Curiosity 2nd Edition: A Resource for Educators: Considering Indigenous Perspectives in Children's Environmental Inquiry is one place of many to start.

- Building my foundation of ecological knowledge by spending time with a place and focusing on what my senses tell me about the world around me, rather than turning first to the guide books.

- Greeting and verbally acknowledging the natural world. Saying good morning to the four directions, and to the trees, and the birds, and so on. Accrediting this as a common practice in many Indigenous cultures (see Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address).

- Asking permission before harvesting something, providing a gift if permission is granted, and saying thank you afterwards (Robin Wall Kimmerer has written about this beautifully in her book Braiding Sweetgrass). Also taking time to thank the forest or other natural areas when we leave them for the day.

- Meeting children (and adults) curiosity and enthusiasm with equal curiosity and enthusiasm to acknowledge that affection and excitement are completely acceptable emotions to have in relation to nature.

- Learning about and reflecting on what it means to build an "ecological identity" (See books by Mitchell Thomashow & Jan White) and actively working to shift my own perspective of the natural world from one based on "utilization" to "relationship" and "kinship".

- Writing and upholding an "Environmental Relationships" policy for my programs. This includes completing and continuously revising an "Environmental Relationships and Impact Assessment" document. There's opportunity to involve children in the development of these documents too!

- There is so much more that I will be adding to this list as I learn and grow. Can you think of anything else?

So, when a group once discovered a vast number of salamanders inhabiting the stream we were exploring, we allowed ourselves to follow our excited enthusiasm and interact with them. We used old yogurt containers to scoop them up for a closer look. I shared how I'd learned that handling salamanders and other amphibians can be harmful because they have permeable skin and chemicals from our hands (often because of bug spray and sunscreen) can be toxic to them.

Some of the children listened to this and refrained from handling them, and others captured and held them anyway.

I could have stepped in and made a hard and fast rule for everyone to leave all salamanders alone. To draw a line between us and the salamanders in an effort to protect them. Mitigate harm in the name of sustainability. If we stay here, on this side, and the salamanders stay there, on that side, then all will be fine, right?

Except that severs the connection between humans and nature... which is the root cause of so many of our social and environmental issues today!

So instead, when one of the salamanders died while being held, we took time to talk about it. We allowed space to feel sadness, and guilt. And together we created a plan to never let another salamander in our care die again. Some of the children buried it ceremoniously. Then we put our hands together and created a pact. We all shouted in unison "Keep Salamanders safe!"

Write your awesome label here.

Then when it was time to leave for the day, we looked out towards the forest and the stream and said, "Thank you."

I went home, inspired and invigorated to do better in the future. I hope the children did too.

References:

Anderson, D., Comay, J., & Chiarotto, L. (2017). Natural Curiosity 2nd Edition: A Resource for Educators: The Importance of Indigenous Perspectives in Children’s Environmental Inquiry (2nd ed.). The Laboratory School at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study.

Taylor, D. E. (2018). Racial and Ethnic Differences in Connectedness to Nature and Landscape Preferences Among College Students. Environmental Justice, 11(3), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.0040

Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address | The American Yawp Reader. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/british-north-america/haudenosaunee-thanksgiving-address/

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Rice, J. (2011, March). Indian Residential School Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/indian-residential-school-truth-and-reconciliation

Thomashow, M. (1995). Ecological identity. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

University of Wales. (2018, March 12). Press Releases 2018 | University of Wales Trinity Saint David. https://www.uwtsd.ac.uk/news/press-releases/press-2018/jan-white-professor-of-practice-at-uwtsd-addresses-early-years-students-in-carmarthen.html

More Posts

WANT TO GET FOREST SCHOOLED TOO?

Subscribe to my email letters, something special from me to you so we can learn together. Each one is filled with heart-felt stories from the forest, resources you may find useful, and things that hopefully bring a smile too.

Thank you!

© by FOREST SCHOOLED